August 5, 2014

by Joanna Birkner

Comments Off on Joanna Birkner ’16: A crash course in Turkish politics (Your guide to the upcoming Turkish Presidential Election)

It was a hot and lazy day in Bursa and I spent the afternoon watching TV and relaxing at home with my host family. For the first time I breached the subject of Turkish politics with them. The conversation was spurred by a nearly two-hour-long televised speech by current Prime Minister and Presidential nominee, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Erdoğan has served as Prime Minister for more than a decade and he is considered Turkey’s most momentous leader since Ataturk. In the middle of Erdoğan’s impassioned speech, my host dad looked at me and said, “The most powerful man in the world is your president, Obama. Second is Tayyip (Erdoğan). Third is Putin. Remember that.”

It was a hot and lazy day in Bursa and I spent the afternoon watching TV and relaxing at home with my host family. For the first time I breached the subject of Turkish politics with them. The conversation was spurred by a nearly two-hour-long televised speech by current Prime Minister and Presidential nominee, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Erdoğan has served as Prime Minister for more than a decade and he is considered Turkey’s most momentous leader since Ataturk. In the middle of Erdoğan’s impassioned speech, my host dad looked at me and said, “The most powerful man in the world is your president, Obama. Second is Tayyip (Erdoğan). Third is Putin. Remember that.”

I can’t defend my host father’s list, but I can attest to the forcefulness of Erdoğan’s leadership. While I don’t claim to be an expert on this subject, living with two different host families on opposing sides of the Turkish political debate has given me valuable insight on the ever-increasing polarization of Turkish politics. This is an exciting and tense time to be in Turkey as the presidential election is just a week away.

What does this election determine?

August 10 will mark Turkey’s first ever direct presidential election. In the past, parliament was in charge of choosing the president. The position has traditionally been ceremonial, with the president serving more as a figurehead than a leader — but that could change if Erdoğan is elected. He intends to amend the constitution to give the president more executive authority as well as make more use of the presidential power to appoint judges and veto laws that are passed by parliament.

The winner needs at least 50% of the votes. If none of the candidates claim half the votes on Sunday, then a run-off election is set to be held on August 24. Many analysts believe that Erdoğan will win handily in the first round. The winner will serve a five-year term.

Who’s in the running?

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is the front runner. His Justice and Development Party (AKP) easily won local elections across Turkey in March. The media strongly favors Erdogan and his face seems to be everywhere—on television commercials and billboards, even minivans that zoom around the city blaring music and recordings of his voice. He is revered by religious conservatives and comes from humble roots in Istanbul. His Islamic agenda has antagonized and alienated the secular elite as well as young middle class liberals and nationalists. Many credit him with Turkey’s economic growth, but after the violent Gezi Park protests in 2013 that left nine dead, and a much-publicized corruption inquiry, Erdoğan is a controversial figure who is held responsible for Turkey’s extremely polarized political landscape.

Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu is a former diplomat who represents the Republican People’s Party (CHP, center-left) and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP, far-right). He was not well known to the Turkish public before this election but promises to offer a middle ground and seek compromise. If he is elected, Turkey would likely have a more tolerant and open future.

Selahattin Demirtaş, an ethnic Kurd, is the third nominee, representing the far-left People’s Democratic Party (HDP). He champions diversity and if elected would certainly work toward ending the disenfranchisement of minorities living within Turkey. Although Kurds make up about 18% of Turkey’s population, political pundits estimate that Demirtas would only garner 5-10% of the vote. Sadly, much of the talk on the street about his candidacy is racially offensive because of his Kurdish background.

What is at stake?

This election represents a large cultural drift in modern Turkey. Under the AKP, rights of women will continue to deteriorate. During a speech in 2010, Erdoğan asserted that he does not believe in gender equality and that men and women simply “compliment” each other. He believes that abortion is murder and has been trying to restrict abortions and other women’s reproductive rights since coming into office. He opposes co-ed college dorms and has repeatedly called on every Turkish woman to have at least three children. Meanwhile nearly 40% of all Turkish women have reported spousal abuse in their lifetimes and domestic violence has claimed the lives of 120 women since January of this year.

To drive home this point, Bülent Arınç, deputy prime minister and co-founder of the Erdoğan’s AKP party, gave a speech in Bursa at the end of July where he said, “[A] woman must not laugh in public … Where are our girls, who blush delicately, lower their heads and turn their eyes away when we look at their faces, our symbols of chastity?” Women on the Internet have responded by flooding Twitter with laughing photos and on August 8 there will be a laughing protest in Istanbul. With Erdoğan in power, Turkey will most likely continue down a more religiously-minded, conservative, and alarmingly authoritarian path. But there will be resistance to this path. My only hope is that this resistance comes with laughter instead of violence.

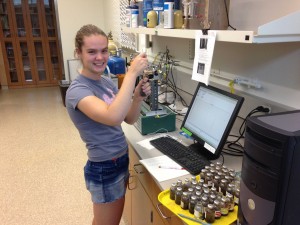

Why I applied for my internship: I had been looking for an on campus job for over the summer for several weeks when I received the mentioned email. My main goal for this summer was to explore one of my many career-related interests, and ecology was definitely high on that list. Working in Dr. Mozdzer’s lab seemed like the perfect opportunity to gain lab experience and get to know myself and my interests a little bit better.

Why I applied for my internship: I had been looking for an on campus job for over the summer for several weeks when I received the mentioned email. My main goal for this summer was to explore one of my many career-related interests, and ecology was definitely high on that list. Working in Dr. Mozdzer’s lab seemed like the perfect opportunity to gain lab experience and get to know myself and my interests a little bit better.